September 30, 2005

September 28, 2005

September 27, 2005

Outline from Irene's Text Chapters Overview Map

Business Communication

- Communication in the Workplace

- Main Forms

- Internal-Operational

- External-operational

- Personal

- Network Of The Organization

- The Formal

- the Informal

- Human Communication Process

- Enter in the Sensory World

- Senses pick up the message and relay it to the brain

- The brain filters the message through all its contents

- knowledge

- emotions

- biases

- such

- This meaning may trigger a response, which the mind then forms

- encodes

- The person then sends by some medium this message into the sensory world of another person

- Within this person the process described above is repeated

- another cycle begins

- The process continues, cycle after cycle, as long as the people involved care to communication

- Basic Truths

- Meaning Sent Are Not Always Received

- Meaning Is In the Mind

- The Symbols of Communication Are Imperfet

- Main Forms

- Adaptation and the Selection of Words

- Basic need for adaptation

- Visualizing the Reader

- Technique of Adapting

- Adaptation Illustrated

- Adapting to Multiple Readers

- Governing Role of Adaptation

- Use Familiar Words

- Unfamiliar Words

- Familiar Words

- Choose Short Words

- Long words

- Short words

- Use Concrete Language

- Abstract

- Concrete

- Use the Active Voice

- Passive

- Active

- Avoid Overuse of Camouflaged Verbs

- Action Verb

- Noun Form

- Wording of Camouflaged Verb

- Camouflaged Verb

- Clear Verb Form

- Select Words for Precise Meanings

- Faulty Idiom

- Correct Idiom

- Use Gender-Neutral Words

- Masculine Pronouns for Both Sexes

- Sexist

- Gender-Neutral

- Words Derived form Masculine Words

- Sexist

- Gender-HNeutral

- Masculine Pronouns for Both Sexes

- Basic need for adaptation

- Construction of Clear Sentences and Paragraphs

- Limiting Sentence Content

- Long and Hard to Understand

- Short and Clear

- Economizing on Words

- Cluttering Phrase

- Shorter Substitution

- Surplus Words

- Needless Repetition

- Repetition Eliminated

- Unrelated Ideas

- Unrelated

- Improved

- Excessive Detail

- Excessive Detail

- Improved

- Illogical Constructions

- Illogical Construction

- Improved

- Making Good Use of Topic Sentence

- Topic Sentence First

- Topic Sentence at End

- Topic Sentence within the Paragraph

- Limiting Sentence Content

- Writing for Effect

- Resisting the tendency to Be Formal

- Stiff and Dull

- Conversational

- Proof through Contrasting Examples

-

- Dull and Stiff

- Friendly and Conversational

-

- The You-Viewpoint Illustrated

- We-Viewpoint

- You-Viewpoint

- Examples of Word Choice

- Negative

- Positive

- Being Sincere

- Overdoing the Goodwill Techniques

- Avoiding Exaggeration

- The Role Of Emphasis

- Emphasis by position

- Space and Emphasis

- Sentence structure and Emphasis

- Mechanical Means of Emphasis

- Coherence

- Tie-In Sentences

- The Initial Sentence

- Abrupt Shift

- Good Tie-In

- Tie-In Sentences

- Resisting the tendency to Be Formal

September 19, 2005

On Textbooks -- from About

Textbooks can cost a small fortune. It seems that every year the required texts get heavier and the prices get higher. According to a study done by Senator Charles E. Schumer, the average student will pay almost $1,000 for books during a single year. An undergraduate student may end up paying up to $4,000 on books before he or she receives a degree. Unfortunately, distance learners don’t always escape this fate. While some online schools offer a virtual curriculum, free of charge, the majority of online colleges still require their students to purchase traditional textbooks with hefty price tags. Books for one or two classes could total in the hundreds. However, showing a little shopping savvy could save you a significant amount of cash

Before you even check the bookstore, take a look to see if you can find the material elsewhere. There are dozens of virtual libraries that offer reference material and literature with no cost to the reader. While newer texts are unlikely to be online, hundreds of older pieces with expired copyrights are all over the internet. The Internet Public Library, for example, offers links to hundreds of full-text books, magazines, and newspapers. Bartleby, a similar site, offers thousands of ebooks and reference materials free of charge. Readers can even download the books for free and view them on their desktop or handheld device. Project Gutenberg provides 16,000 e-books free for download, including classics such as Pride and Prejudice and The Odyssey. Google Scholar is offering an ever-increasing database of free academic articles and ebooks. If your curriculum consists of an over-priced packet of photocopied articles, check to see if the material is available here before forking over the cash.Another alternative is trying to find a student in your area who purchased the book during a previous semester. If your online school has message boards or other means of communicating with your peers, you may ask students who have taken the course before if they would be willing to sell the book at a discounted price. If you are near a physical college campus that offers courses similar to your online classes, scouring the campus for flyers advertising student-sold books may be your ticket to saving a few dollars. Before you begin a random search, find out what buildings house the departments that are likely to require your books. Students often post advertisements on the walls of their old classrooms.

http://clk.about.com/?zi=1/XJ&sdn=distancelearn&zu=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.alibris.com

http://clk.about.com/?zi=1/XJ&sdn=distancelearn&zu=www.ebay.com

http://clk.about.com/?zi=1/XJ&sdn=distancelearn&zu=www.half.com

http://clk.about.com/?zi=1/XJ&sdn=distancelearn&zu=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.textbookx.com%2F

http://clk.about.com/?zi=1/XJ&sdn=distancelearn&zu=www.allbookstores.com%2F

http://clk.about.com/?zi=1/XJ&sdn=distancelearn&zu=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.gutenberg.org%2F

scholar.google.com

http://clk.about.com/?zi=1/XJ&sdn=distancelearn&zu=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ipl.org%2F

http://clk.about.com/?zi=1/XJ&sdn=distancelearn&zu=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bartleby.com%2F

http://clk.about.com/?zi=1/XJ&sdn=distancelearn&zu=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.comparetextbook.com%2F

http://clk.about.com/?zi=1/XJ&sdn=distancelearn&zu=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.amazon.com

September 16, 2005

September 15, 2005

Veronika's Letter of Introduction

Veronika Takmazyan

25 Poncetta, Apt #129

Daly City, CA 94015

September 15, 2005

Dr. Sylvia Schoemaker

Lincoln University

401 15th Street

Oakland, CA 94612

Dear Dr. Schoemaker:

I’d like to introduce myself. My name is Veronika Takmazyan. I was born in Sochi, Russia in 1985. After graduating from high school I entered to Sochi State University for Tourism and Recreation, majoring in management. In 2005 I graduated with a B.A. and decided to try the Work and Travel program, provided by our university. My aim was to improve my language and to continue my education. I chose Lincoln University because it was ideal for me –a diverse student body, stimulating learning environment and access to a strong alumni network.

Working closely with students from around the world and from different industries helps me learn more about team work and the importance of aligning objectives and clear communication. then, after at least five years of work experience, I'll have the foundation that will help me have a better future.

Sincerely yours,

Veronika Takmazyan

Willy's Letter of Introduction

WILLY JOSEPH

2851 STERNE PLACE

FREMONT CA 94555-1425

(510) 364-4396

Lincoln University

Dr. Sylvia Schoemaker

401 Fifteenth Street

Oakland, CA 94612

September 14, 2005

Dear Dr. Schoemaker:

My name is Willy Joseph. I was born in India. I came to America twenty years ago. After graduating from high school I went to Ohlone junior college for a short while. Mostly after high school I have been working in the security field. Just now I decided to go back to school. I made a decision to attend Lincoln University after doing some research. The degree I’m studying for is Associate of Science in Diagnostic Imaging.

Sincerely,

Willy Joseph

September 14, 2005

Letter of Introduction

E-mail your completed letter to the E93 students and to me at: drsylviasf@gmail.com

September 12, 2005

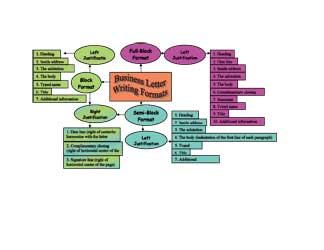

Letter Formats

Full block letter style example:

http://bcomca.blogspot.com/2006/10/full-block-letter-style.html

September 11, 2005

Letters of Recommendation -- from Chronicle of Higher Education

Getting Great Letters of Recommendation

By RICHARD M. REIS

We were three Ph.D. students from Stanford applying for the same academic position at a Canadian university, yet I was the only one who was asked to come for an interview. I wasn't the brightest, I didn't have the best grades, and I didn't finish my dissertation in the shortest time, but when it came to enthusiasm, quickness on my feet, and outright creativity, I knew I was tops among the three. However, none of these traits were reflected in my transcript. The only way interviewers were going to find out I had these qualities was through my letters of recommendation. It was those letters that got me -- and not my competition -- to the next stage.

Letters of recommendation are often the first independent assessment of your capabilities, performance, and potential that are seen by a search committee. It's important that they be first-rate. If there is to be any follow-up by telephone or in person, it will most likely come if your letters are from mentors who say great things about you.

Anything less just won't cut it in today's competitive job market in the sciences. The critical role of these references is captured nicely by Irene Peden, professor emerita of electrical engineering at the University of Washington, who says a good recommendation letter is enthusiastic and does not "damn the subject with faint praise or attempt to give a balanced view by articulating the candidate's shortcomings as well as strengths. There are appropriate places for that, but ... not in letters of recommendation."

What do search committees look for in letters of recommendation? They want to know how you compare with others in your field of roughly the same experience -- i.e. your competition. What are your capabilities as a scientist? Do you show promise of continued development and professional growth? Do you have the potential to direct the work of others? What is your interest in, and hopefully experience with, teaching and working with students? Perhaps they have seen you address classes or seminars and can report on your style and effectiveness as a lecturer. Any information about your services to professional societies and journals would also be useful.

As Ms. Peden notes, you don't want to be damned with faint praise. Phrases such as "is reliable," "can be counted on to be in the lab every day," and "works well with other researchers" are OK but only if they are followed up with specific anecdotes that show how you really stand out.

All of your letters will have some things in common since they are all about you. This commonality is good, since it reinforces a positive image of your work. However, each letter should also be unique. Specific aspects of your education, character, and capabilities, as seen from the recommender's perspective, should be included.

So how, and from whom, do you obtain great letters of recommendation?

The key to getting such letters is to treat the process with forethought, not as an afterthought. You need to know your recommenders well enough over time so that they can say substantial things about you, backed up by firsthand experience and a reasonable amount of detail.

In principle, this sounds easy enough, since most of you will have been in the same working environment as your potential recommenders for a minimum of one, and more typically, three to four years. However, just being around a future letter writer is not enough. Recommenders may be asked to write a dozen or so letters each year, and you need to stand out in their minds as unique. That means making sure that over time these people become aware of your activities and accomplishments.

This is where forethought comes in. When you give presentations at university seminars or professional conferences, take note of who is in the audience. Follow up by sending these people copies of your talk. Take time to socialize with junior and senior colleagues at laboratory or department functions. Also, be sure to discuss your evolving career interests with junior and senior faculty members. Finally, don't be afraid to ask senior scientists for advice about various career possibilities. The vast majority will welcome the opportunity to chat, (after all, they were once asking for the same guidance) and in the process will come to know you in a more well-rounded way.

How many letters of recommendation should you obtain? Three to five is usually the right number. Obviously your primary academic/dissertation adviser should write one of them. So should your supervisor if you are a postdoc. Someone who addresses your teaching interests and capabilities would be another. Also, consider obtaining a letter from someone in industry if you have had substantial interactions with the person during your graduate or postdoc experience.

What happens if your relationship with your primary adviser or postdoc supervisor is troubled in some way? This is a difficult question. Mary Morris Heiberger and Julia Miller Vick, who write this site's Career Talk column, addressed this problem briefly in a September 18, 1998, column. They recommend that you "ask the most senior person in your department whom you trust to write a letter for you that will, according to that person's best judgment, address the situation directly or indirectly."

I also suggest that you take the approach of asking different people to write about the different aspects of your work. In this way, important people with whom you have had some difficulty personally could be asked to write specifically about a success of yours in the laboratory, for example.

Another question that sometimes arises is whether to ask a "big name" scientist who may not know you well, versus someone of lower stature who is more familiar with your work. In almost all cases you should go with the people who know you best, who can demonstrate a personal knowledge of you gained through a long-term working relationship.

Keep in mind, however, that you don't always control who will be asked for their opinion about you. A senior, highly respected scientist in your department or laboratory, who may not even know you well, may be asked about you informally even if you did not list the person as a recommender. It doesn't hurt to make sure that such people are aware of your work through one or more of the approaches noted above.

The timing of your request for letters can be important. If you have just accepted a postdoc position, now is the time to get letters into your file from the people you knew as a graduate student. Even if they aren't used for a few years, they will capture a crucial period in your education. You want to have such letters put in your file while the memory of your recommenders is fresh. You can always go back to them for updates if appropriate. In some cases, you may want your recommenders to write two letters, one for a future academic position and one for a forthcoming postdoc or industry position. If you are completing a postdoc, then clearly your current supervisor will write a letter about your research experiences, but he or she could also talk about your academic interests.

At least a few months in advance of the need for such letters, you should sit down and have a thoughtful conversation with your potential recommenders about the kind of job you seek. Discuss the important aspects of your relationship as they relate to your application for an academic, postdoc, or industry position.

If you are seeking a professorship, talk about the desired balance between teaching and research, and graduate and undergraduate emphasis. If you are looking for a position in government or industry, talk about opportunities for both basic and applied research, and about possible publication limitations in a proprietary environment.

Don't just supply your letter writers with a copy of your C.V. Also provide one or two pages, perhaps with the main points in bulleted form, about things not in your C.V. that you wish to have expanded in the recommendation letters. Remind them of the particular way you approached and solved a problem, the initiatives you took with colleagues, and the feedback you received on your teaching evaluations.

Remember, your C.V. tells what you did. Your letters of recommendation tell how well you did it.

Strike the right balance in your approach. While you don't want to appear to tell your recommenders what to say or how to write letters, you do want to give them needed background (and reminders) about points they will want to write about anyway. Most recommenders appreciate this "assistance" if it is presented in the proper way.

Finally, be sure to write a formal thank-you note to your letter writers. Keep in touch with them as well. They are interested in the outcome of their efforts on your behalf, and no matter where you go next, they will continue to be your professional colleagues.

Read previous Catalyst columns.

Have a question or a suggestion for Richard Reis? Please send comments to catalyst@chronicle.com

Richard M. Reis is director for academic partnerships at the Stanford University Learning Laboratory, and author of Tomorrow's Professor: Preparing for Academic Careers in Science and Engineering, available from IEEE Press or the booksellers below. He is also the moderator of the biweekly Tomorrow's Professor Listserve, which anyone can subscribe to by sending the message [subscribe tomorrows-professor] to Majordomo@lists.stanford.edu

September 06, 2005

Business Communication In-class Assignment 1

September 05, 2005

Full Block Letter Style

111 Any Street -- San Francisco, CA 94118 -- (415) 221-1212

May 22, 2005

John Smith

XYZ Company

123 Anything Avenue

San Francisco, CA 94115

Dear Mr. Smith:

Blah blah blah. With the full- blocked letter style each paragraph begins at the left

margin.. Some more important information continues in the first paragraph for two to

four sentences.

Blah blah blah. Between paragraphs there is additional line space indicating a new

paragraph. The date of composition, receiver’s address, complimentary close, sender’s

name, and sender's title, and additional information are also left aligned. This makes this

letter style the easiest to format.

Sincerely yours,

Terry D. Sender

Terry D. Sender

Project Manager

TDS:YS

CC: A. Receiver, B. Receiver

BComm Text Resources

- Guide to Avoiding Plagiarism (pdf)

Use this concise four-page handout to help prevent problems with plagiarism. In taking a positive step to educate student on why crediting sources is necessary and to give examples of what is appropriate, you will spare yourself and yours students much grief over this later. In addition to handing it out, you may want to make it available to them on Blackboard, WebCT, or a class website. - Diagnostic Test of Correctness (Word)

This diagnostic handout is identical to the one found in the text at the end ( p. 494) of Chapter 17 on Correctness. One might want to use it in class during the first week to learn where students correctness skills start. The answers appear in Appendix A (p. 552) - Oral Presentation Evaluation Form (MS Word) (pdf)

This handy form can be used as is or modified for your needs to evaluate individual oral presentations.

BComm Links

Here are some interesting and unusual sites for you to visit.

Grammar sites:

Big Dog’s Grammar

This is a great site to polish all of the grammar rules you didn’t know or have forgotten.

Common Errors in English

This site is by Paul Brians, a Professor of English at Washington State University. Read this opening page (and read all of it) for a very insightful look as to why Professor Brians created it, and how it can help you. One of Professors Brians’ reasons? “ . . . to help you avoid low grades, lost employment opportunities, lost business, and titters of amusement at the way you write or speak.”

Purdue University’s OWL

This site comes from Purdue University and is their “OWL” or Online Writing Lab. It has a lot of good information, including: grammar, spelling, and punctuation, research and documenting sources (including MLA and APA styles), and professional writing (such as resumes and cover letters).

Guide to Grammar and Writing

Another great site for grammar and writing hints, PowerPoints, and search devices. This one is by Charles Darling, Professor of English at Capital Community College.

Business Communication Concepts

Language

Patterns in Language

Changing habits for business communicators

The microcomputer in communication

The information cycle

Electronic communication and word processing Written business communications

- Types

- Steps

- Grammar

- Mechanics

- Purpose

- Format

Format of business letters

Types of business letters

- Informative letters

- Persuasive letters

- Problem-solving letter

- Special occasion Style of business letters

- Steps

- Types

- Parts of the formal business report

- Primary

- Secondary

Oral Communication.

Communication Theory

Communicative roles

Communicative climate

Informal channels of communication

Interviews

Meetings

Formal oral communication

Course Website

Business Communication -- Virtual Sylvia -- ViaSyl

Primary E93: Business Communication objectives are to improve your ability to comprehend and produce effective written and oral business communications, to evaluate business messages within appropriate contexts, and to apply systematic language processing strategies for critical thinking, problem solving and decision making. Upon successful completion of this course, the student will be able to:

1. Learn to analyze the communicator, audience, purpose, context, and strategies of business communications.

2. Select appropriate content and detail for varied situations.

3. Recognize appropriate organization techniques, formats, and strategies for varied situations.

4. Become aware of tone and style choices in varied communications.

5. Gain experience in group projects. 6. Evaluate accurately the communications of self and others.

Course Policies

STUDENT RESPONSIBILITIES

Students are expected to attend class, complete assignments, and to participate in group work in a productive manner.